February 16, 2023

Photo Credit: William Vandivert, The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

Imagine an American city that, when founded in 1701 by French colonists, would be laid out in such a way that would be informally known as the “Paris of the West.” A city with such a valuable waterfront location and border crossing with Canada that would grow to become one of the most important logistics centers in the country. A city that would become the birthplace of the American automotive and mobility industry, and countless forms of music would owe their birth to it. A city of triumph that would not only become majority Black but also the Blackest major city by percentage in America.

That city would be Detroit, Michigan. From Telegraph to Mack Avenue, Motor City has a rich history from starvation to innovation, and one of its most notable eras was the rise and fall of Black Bottom. During this Black History Month, we should discuss this significant foundational Black community of Detroit.

After a period of reconstruction and seemingly incurable anti-Black hostilities in southern states, including Jim Crow laws, economic exclusion, and oppressive domestic terrorism, many African Americans sought a better life in the North. Combined with a promise of economic opportunities and a more friendly social environment, many took up their belongings and headed for the largest northern cities in the country at the time, which included New York City, Washington, D.C., Cleveland, and of course, Detroit.

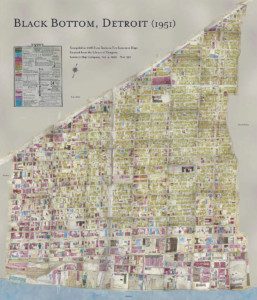

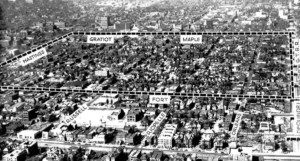

Detroit was the largest city in Michigan and was one of several cities that saw a large influx of African American migrants, who were attracted by the city’s growing industrial economy with the potential of better job opportunities. However, even with a metropolis as large as Detroit, the Black community was forcibly boxed into specific areas of the city. One of those areas was a neighborhood known as Black Bottom, which was in the lower east side of Detroit. This area would become the socioeconomic epicenter for the Black community as they arrived and built lives in Detroit, starting back as far as the early 1900s. Ironically, the name Black Bottom had nothing to do with African Americans inhabiting the neighborhood but rather was given by the French settlers for the rich dark soil found in the area.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress

The key attraction of Black Bottom was it being one of the few neighborhoods in Detroit that would accept African American residents at that time. Redlining was in full swing, along with its undergirding racism that had made life tough in the South. As such, despite there already being immigrants of Eastern European, Jewish, and even Italian descent living in Black Bottom before the Great Migration, over time, as more African Americans began arriving, these original groups moved out.

The owners of these vacated premises were willing, unlike many of the surrounding neighborhoods’ residents, to sell or lease their spaces to African Americans. This created the opportunity to secure more housing and business space, furthering a sense of belonging and safety and fostering a magnetic vacuum for more Black residents to come to the neighborhood. Around 1908, the city had less than 10,000 African American residents, but that would grow to well over 112,000 by 1930, with many of those living in the bourgeoning Black Bottom.

Although this image of community is an inspiring picture to paint in our minds, the community was far from a wealthy and equitable utopia. At the height of Black Bottom’s heyday, Detroit was a city of over 1.5 million people but still predominantly white, with less than 10% of the city being African American. However, half of Black Detroiters lived in Black Bottom. Unfortunately, poverty and crime in the neighborhood were not insignificant, and it was easily one of the poorer and denser areas of the city.

In addition, despite having better prospects in Detroit than in many southern cities, African Americans still faced discrimination in both the labor force and banking services, which further hindered their ability to maintain existing, buy new, or outright move from their homes. In fact, many families shared single dwellings with multiple other families and were well behind in maintenance and upkeep. Due to the conditions of many structures in Black Bottom, the Detroit city government was able to easily declare many of the homes as substandard, designating entire areas of Black Bottom as slums.

Photo Credit: © Detroit Public Library, Burton Historical Collection

Nevertheless, Black Bottom was still a thriving community unto itself. Not only was it where thousands of African Americans laid their heads, but it also featured a thriving African American cultural scene and business corridor shared with neighboring Paradise Valley, which was known for its vibrant music with jazz and blues clubs and cabarets lining the streets and where many musical greats would frequent.

There were also many non-entertainment businesses, including grocery stores, beauty shops, and barber shops. The community was a close-knit one, with residents often gathering in the local parks and community centers to socialize and participate in cultural events and activities. You could say the sheer will of Black Detroiters to live their lives despite discrimination and other challenges related to it birthed the unwavering grit and tenacity that Detroit is known for today.

In 1946, while African American newcomers were still arriving daily, something new got underway. Something that would begin to destroy Black Bottom and send community members scattering into new low-income housing projects. The then-mayor of Detroit, Ed Jeffries, gained an idea from a real estate developer to acquire all of the buildings in Black Bottom and demolish them with a plan to completely redevelop the area. The mayor, enabled by a distorted and racially-biased lens casting the residents of Black Bottom as belligerent, unintelligent liabilities to the city and also not seeing favorable tax income from the area, brought the idea to the City Council.

Photo Credit: Walter P. Reuther Library

The Council agreed and greenlit what they could at the time. Eventually receiving aid from the Federal Housing Act of 1949, the city of Detroit embarked on a mission to clear out tens of acres of land in Black Bottom by aggressively and excessively condemning structures to make way for a myriad of new developments. Following that, the Federal Highway Act of 1956 funded the construction of the I-375/Chrysler Freeway in the early 1960s. This highway would become a fatal blow to Black Bottom by bisecting the neighborhood and displacing thousands more residents. By then, Black Bottom was no longer as recognizable as it had once been.

The massive landscape change of razing Black Bottom bolstered a series of events that have created what is today’s Detroit. In 1950, Detroit was the nation’s fourth-largest city. After that point, the population started to decline. Notably, white flight took place; meanwhile, Black people kept immigrating into the city. This would lead to a population flip just before 1980, wherein Blacks would finally become the majority racial population of Detroit. However, as whites kept leaving the city, the total population would eventually drop below 1 million in the 90s, which would become a liability for a city built for two million people.

Photo Credit: Detroit’s Great Rebellion

So it turns out the racial divisiveness that would destroy Black Bottom would become a major contributor to the overall decline of Detroit, over time leading to the removal of wealth, lost tax revenue, and blighting neighborhoods. White families fled to the suburbs, leaving many African Americans behind to deal with the ensuing aftermath of an eroded tax base and evaporating economic opportunities for them and their children, further exacerbating the trauma-induced dysfunctions of general poverty.

Photo Credit: Detroit’s Great Rebellion

Detroit would continue onward under a growing African American population to tame increasing crimes and dilapidation to get its city under control.

The legacy of Black Bottom lives on, but only in the stories and memories of historians, former residents, and the cultural contributions that it made to the city of Detroit. Today, a plaque located in Lafayette Central Park, 1500 E. Lafayette, Detroit, serves as a memorial to the neighborhood and its residents. Additionally, several community organizations and activists continue to work to preserve the history of Black Bottom and other African American neighborhoods in Detroit.

In a way, we might say Black Bottom was the birthplace of modern Detroit. Its destruction further inflamed racial tensions to the culmination of the 1967 Uprising, which in turn kicked off massive growth in white flight. The shifting demographics eventually led to the election of the city’s first Black mayor, Coleman A Young. Everything after that is …. Well, the next chapter of history – which isn’t our focus today. 😊

But in conclusion, the Black Bottom neighborhood of Detroit was a thriving and vibrant community that was home to thousands of African American residents for several decades. Despite the challenges that it faced, Black Bottom played a significant role in the history of Detroit and the larger African American community, and its legacy continues to be impactful, remembered, and celebrated today.

It showed that African Americans could set up and maintain everything we needed, from doctors and dentists to tailors and carpenters. Black Bottom perfected the tenacious glue that has been passed down through generations and keeps this city going. The destruction of Black Bottom and other African American neighborhoods in Detroit must serve as a reminder of the clear case for socioeconomic racial justice and equality in the United States and the importance of preserving the history and cultural contributions of these communities for future generations. Welcome to Detroit.

Written by Black Young Professionals of Metro Detroit